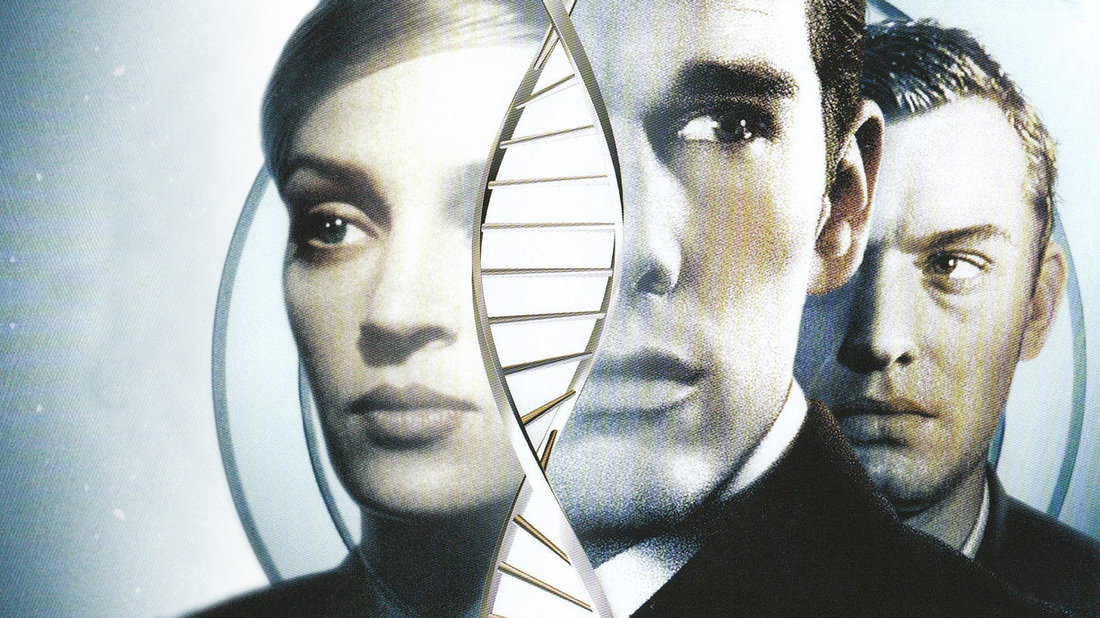

In the 1997 film “Gattaca,” Vincent, the narrator and protagonist, tells the audience that he will “never understand what possessed [his] mother to put her faith in God’s hands, rather than her local geneticist.”

“Gattaca” is a film about genetic engineering and the human spirit set in the “not-too-distant future.” Well, as former Washington Redskins’ coach George Allen used to say: “the future is now.”

“Gattaca” is a film about genetic engineering and the human spirit set in the “not-too-distant future.” Well, as former Washington Redskins’ coach George Allen used to say: “the future is now.”

|

In the movie, a process known as pre-implantation genetic diagnosis allows prospective parents to choose those embryos containing the best-possible combination of hereditary traits. But because Vincent’s parents conceived him the “old-fashioned” way, in the back seat of a car, he’s relegated to second-class citizen status.

|

“Gattaca” is considered to be one of the best science fiction films of the past twenty-five years, but we seem to be on the verge of turning the world it depicts into science fact.

A recent series of articles at Time magazine’s website discussed the potential and pitfalls of a new technology called “whole-genome sequencing” or WGS. WGS can analyze a person’s entire genome and identify genetic risk factors for diseases such as diabetes and cancer.

WGS isn’t new—it’s been around for a decade. Remember the Human Genome Project? Same idea. But the millions of dollars that process used to cost and the ten years it took to complete has been reduced to about $7,500 today. And you can get the results in a few weeks. So, in the not-too-distant future anyone with curiosity and a credit card will be able to have his or his children’s genome mapped.

A recent series of articles at Time magazine’s website discussed the potential and pitfalls of a new technology called “whole-genome sequencing” or WGS. WGS can analyze a person’s entire genome and identify genetic risk factors for diseases such as diabetes and cancer.

WGS isn’t new—it’s been around for a decade. Remember the Human Genome Project? Same idea. But the millions of dollars that process used to cost and the ten years it took to complete has been reduced to about $7,500 today. And you can get the results in a few weeks. So, in the not-too-distant future anyone with curiosity and a credit card will be able to have his or his children’s genome mapped.

And then what? Well, that’s the real question. Reading the pieces in Time I was struck by how much life was imitating art.

For starters, the rationale being offered was let’s do what’s best for our children. That’s naive at best, and willful self-deception at worst. While this may lead to a better genetic diagnosis, there’s very little, if any, actual healing going on here. Why? Because no one’s talking about repairing genetic damage. That’s far beyond our capabilities. For example, when geneticists recently announced that they had successfully removed the extra copy of chromosome 21 in cell cultures derived from a person with Down syndrome, they explicitly denied that this “would lead to a treatment for Down syndrome.”

So what WGS promises—or threatens, depending on your point of view—is to “detect an increased risk not just of childhood diseases but also of disorders that may not manifest for decades, if at all.”

Let’s be honest: the pre-diagnosis we already employ does not lead to healing, but to elimination. What happens to unborn babies diagnosed with Down syndrome? Some 92 percent of them are aborted. And WGS offers pre-diagnosis of conditions that may not manifest for decades, if at all.

What do we think will happen to these children? And what about that “if at all” part? As Time magazine put it, “science doesn’t know enough to yet interpret all the results.” Some mutations are definitely bad news; others are harmless, and we are more-or-less clueless about the rest.

And what’s more, even mutations linked to illnesses such as cancer are just that, linked—which is not the same thing as being caused by the mutation. Identical twins share the same genome, but one can get cancer while the other remains cancer-free. Why is still a mystery.

Anyone who thinks that the widespread adoption of WGS, especially if it’s used in utero, won’t result in discrimination against the already-born and death of countless more unborn is kidding himself. As families growing smaller and health care eats more and more of our GDP, the pressure to use WGS in ways that the movie “Gattaca” envisioned will be almost-irresistible.

The future is now. God help us all.

For starters, the rationale being offered was let’s do what’s best for our children. That’s naive at best, and willful self-deception at worst. While this may lead to a better genetic diagnosis, there’s very little, if any, actual healing going on here. Why? Because no one’s talking about repairing genetic damage. That’s far beyond our capabilities. For example, when geneticists recently announced that they had successfully removed the extra copy of chromosome 21 in cell cultures derived from a person with Down syndrome, they explicitly denied that this “would lead to a treatment for Down syndrome.”

So what WGS promises—or threatens, depending on your point of view—is to “detect an increased risk not just of childhood diseases but also of disorders that may not manifest for decades, if at all.”

Let’s be honest: the pre-diagnosis we already employ does not lead to healing, but to elimination. What happens to unborn babies diagnosed with Down syndrome? Some 92 percent of them are aborted. And WGS offers pre-diagnosis of conditions that may not manifest for decades, if at all.

What do we think will happen to these children? And what about that “if at all” part? As Time magazine put it, “science doesn’t know enough to yet interpret all the results.” Some mutations are definitely bad news; others are harmless, and we are more-or-less clueless about the rest.

And what’s more, even mutations linked to illnesses such as cancer are just that, linked—which is not the same thing as being caused by the mutation. Identical twins share the same genome, but one can get cancer while the other remains cancer-free. Why is still a mystery.

Anyone who thinks that the widespread adoption of WGS, especially if it’s used in utero, won’t result in discrimination against the already-born and death of countless more unborn is kidding himself. As families growing smaller and health care eats more and more of our GDP, the pressure to use WGS in ways that the movie “Gattaca” envisioned will be almost-irresistible.

The future is now. God help us all.